Shouting in silence

Visualising Diaspora

The Western Australian landscape provides physical and emotional space for Layli Rakhsha to reflect on her experiences of migration. She routinely works out in the bushland, photographing and painting in solitude, the environment modulated with gently whispered rhymes. She tells us that she often recites Rumi’s poetry as she works. This is an important interpretive cue. The whispered Persian poems function as narratives of reassurance in unfamiliar locales. Meaning can only be routed through such familiar paradigms, thought processes, and cultural associations. For Rakhsha, specific lines of poetry speak to particular imagery. They are not indiscriminate pairings. Understanding the Australian landscape, and her place within it, can only be processed in this specific way, at this particular point in time.

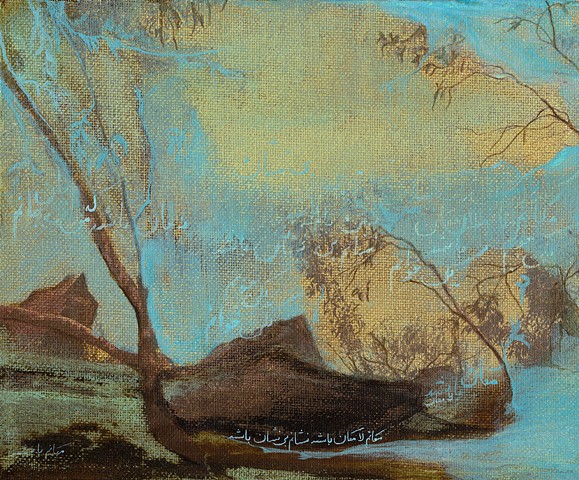

In Rakhsha’s artworks, the bushland becomes a context for the ongoing project of negotiating self-identity. The lapis lazuli transcriptions of Rumi’s poems serve as trace and testimony to these contingent negotiations. The Persian texts are delicately handwritten using this mineral pigment, which has been specially brought by Rakhsha from Iran to Australia. Like the pigment, the writing infers the process of traversing cultural landscapes. In some of her artworks, the superimposed calligraphic texts are barely legible, blending almost imperceptibly into the background. Some of the poems appear to be fragmented, broken in parts. In other works, the texts boldly assert their presence, prominent in their central positioning in the Australian landscape. In my view, these visual forms refer to the complicated range of certainties and uncertainties that make up migrant self-identity. Rakhsha’s artworks collectively represent the ‘here and there’ and ‘here, not there’ dynamic at the core of the diasporic condition. They are paradoxically clear in visualising the sense of profound ambivalence that many diasporic subjects – including new migrants such as Rakhsha – experience in very real terms on a daily basis.

At the same time, these are images of hope. The self-professed nostalgic impulse in Rakhsha’s work is a way of bringing the past into the framework of the present in order to construct a future rich with possibilities. Her work acknowledges that self-identity has its own socially mediated, and personally experienced, cultural history, which in turn serves as a continual source of contemporary reference, be it to embrace, celebrate, fault, quarrel with, rectify, redress, adapt, or learn from. This is a story about negotiating complexity, about many ways of looking, speaking, and thinking, which is surely worth telling, again and again, especially today when fear-driven people are choosing to believe that national identity needs to be safely and securely anchored in the fatal cultural shore of Monolingual Australia.

Dr Dean Chan

Edith Cowan University

September 2006